Great Bear Rainforest and Haida Gwaii

Located on Canada’s Pacific Coast, the Great Bear Rainforest is one of the largest remaining temperate rainforests left on Earth.

A Rare and Globally Significant Temperate Rainforest

Here, trees up to 1,000 years old tower as high as skyscrapers. Valley bottoms (and there are over 100 large valleys and hundreds of small ones) sustain more biomass than any other terrestrial ecosystem on earth. Streams and rivers sustain 20 percent of the world’s wild salmon. Forests, marine estuaries, inlets, and islands support tremendous biological diversity including grizzly bears, black bears, white Kermode bears (also known as Spirit Bears), unique wolf populations, 6 million migratory birds, and a multitude of unique botanical species. The Great Bear Rainforest is truly an ecological treasure.

For millennia, these riches of the Great Bear Rainforest have supported equally rich human cultures. The north and central coast of what is now known as British Columbia and the archipelago of Haida Gwaii are the unceded traditional territories of more than two dozen coastal First Nations. Outside of Prince Rupert—the region’s only urban centre—First Nations comprise the majority of the region’s population living in small, isolated communities such as Klemtu, Bella Bella, Hartley Bay, and Rivers Inlet, accessible only by air or water.

Historically, First Nations carefully managed the abundant natural resources of both land and sea, relying on their knowledge of seasonal cycles to harvest a wide variety of resources without depleting them. They had absolute power over their traditional territories, resources and right to govern, to make and enforce laws, to decide citizenship and to manage their lands, resources and institutions.

Modern times brought newcomers to the Great Bear Rainforest and Haida Gwaii. They came to log the vast tracts of forest and fish the abundant salmon runs. Throughout much of the last century, pulp mills, sawmills, logging camps, canneries, and mines extracted resources from First Nations’ traditional territories despite their protests. While early resource extraction turned profits for companies and provided employment, there were few benefits to First Nations, whose communities suffered extensive economic, social and cultural damage.

Growing Conflict and the Urgent Need for a New Approach

By the 1990s, the need for a shift was dramatically clear. The region’s economy had dwindled to isolated logging camps, a much-reduced fishing fleet, and a handful of tourist lodges scattered through the region. Most First Nations communities were suffering from high unemployment and low graduation rates, limited infrastructures, poor access to healthcare, substandard housing, and low incomes. Piecemeal attempts at economic reconstruction had all failed and, with unemployment rates as high as 80 percent, no group of people in Canada faced a more urgent economic crisis.

The 1980s and early 90s were an era of conflict in British Columbia’s rainforests. As public concern erupted over logging methods, forest companies were forced into the media spotlight, where they defended their practices and challenged their critics. On Haida Gwaii, Haida Elders and youths stood side by side with environmental groups to block the logging trucks and protect large portions of Haida Gwaii. Following in the Haida’s footsteps, activists fought valley-by-valley to protect the remaining 13 intact watersheds on Vancouver Island, culminating in 1993 when over 900 people were arrested trying to prevent logging in Clayoquot Sound. It was the largest mass arrest in Canadian history. And it was time for change.

In hopes that a comprehensive plan with broad-based support might help resolve such environmental disputes, the BC government initiated a province-wide, strategic land-use planning process in 1992. Unlike many other jurisdictions, most of BC’s land base is publicly owned, with unresolved Aboriginal Rights and Title, and 95 percent of BC’s commercial forests are found on public land. This provided a strong incentive for multi-party planning, especially if decisions were to be sustained.

For many years, First Nation communities worked in isolation from one another. But in 2000, leaders from First Nations communities throughout the Great Bear Rainforest gathered for the first time to discuss the shared problems of high unemployment, lack of economic opportunities, and lack of access to resources.

From the outset, the goal of the First Nations was to restore and implement responsible land, water, and resource management approaches on the Central and North Coast of British Columbia, and Haida Gwaii that are ecologically, socially, and economically sustainable.

First Nations wanted to promote economic development on the coast while at the same time protecting the environment and quality of life of those who lived there. They agreed they needed to create increased economic development opportunities and create more jobs for First Nations people and others. They recognized they needed to sit down and work towards mutually acceptable solutions and that, if they did so, these issues could and would be resolved.

As these leaders discussed their communities’ plight, it became clear that they were stronger together. A coast-wide alliance was formed: the Coastal First Nations (Great Bear Initiative Society; formerly Turning Point Initiative). The goal of this new group was to restore and implement ecologically, socially, and economically sustainable resource management approaches on the Central and North Coast and Haida Gwaii. The alliance included the Wuikinuxv Nation, Heiltsuk, Kitasoo/Xai’xais, Gitga’at, Haisla, Metlakatla, Old Massett, Skidegate, and Council of the Haida Nation. (Haisla is no longer a member of Coastal First Nations).

In the southern region of the Central Coast, First Nations leaders established the Na̲nwak̲olas Council, representing (at the time) ‘Namgis First Nation, Mamalilikulla-Qwe-Qwa Sot’Em First Nation, Tlowitsis First Nation, Da’naxda’xw First Nation, Gwa’sala-Nakwaxda’xw First Nation, Kwiakah First Nation, and K’omoks First Nation. (Today Na̲nwak̲olas Council is comprised of five member Nations: Mamalilikulla First Nation; Tlowitsis Nation; Da’naxda’xw Awaetlatla Nation; Wei Wai Kum Nation; and K’ómoks Nation).)

Creation of Coast Funds

First Nations and others had long challenged environmental groups to demonstrate that conservation initiatives could promote economic diversification and deliver benefits to communities rather than hinder economic development. In response to this challenge, environmental groups promoted the idea of attracting conservation financing capital.

To move this concept closer to reality, the Conservation Investments and Incentives Initiative (CIII) was created by First Nations, the BC government, environmental groups, and the forest industry. The coalition of environmental groups (Rainforest Solutions Project) comprised of Sierra Club BC, Stand.earth and Greenpeace; the alliance of forestry companies (Coast Forest Conservation Initiative) is formed of BC Timber Sales, Catalyst Paper, Howe Sound Pulp and Paper, International Forest Products and Western Forest Products. Together they form the Joint Solutions Project (JSP). The first task of the initiative was to explore the legality and feasibility of conservation financing.

Conservation financing meant more than simply injecting money into the local economy—an approach that had been tried unsuccessfully in the past. Instead it linked clear, lasting conservation commitments to new investments supporting innovative new businesses and building conservation management capacity in First Nation communities. Because some models of business opportunities envisioned under conservation financing were unprecedented, Coastal First Nations did some pilot projects and tried out new business concepts such as shellfish aquaculture and research into harvesting non-timber forest products. They also explored pilot projects with Ecosystem-Based Management (EBM) forestry.

In February 2006, the BC government, First Nations, environmental groups and forest companies stood together to announce the Great Bear Rainforest Agreements. It was the culmination of over a decade of work. More directly, it was the outcome of a year and a half of negotiations between First Nations and the BC government, which used the consensus recommendations of the land-use planning processes along with First Nations’ own land use plans to arrive at the final agreements.

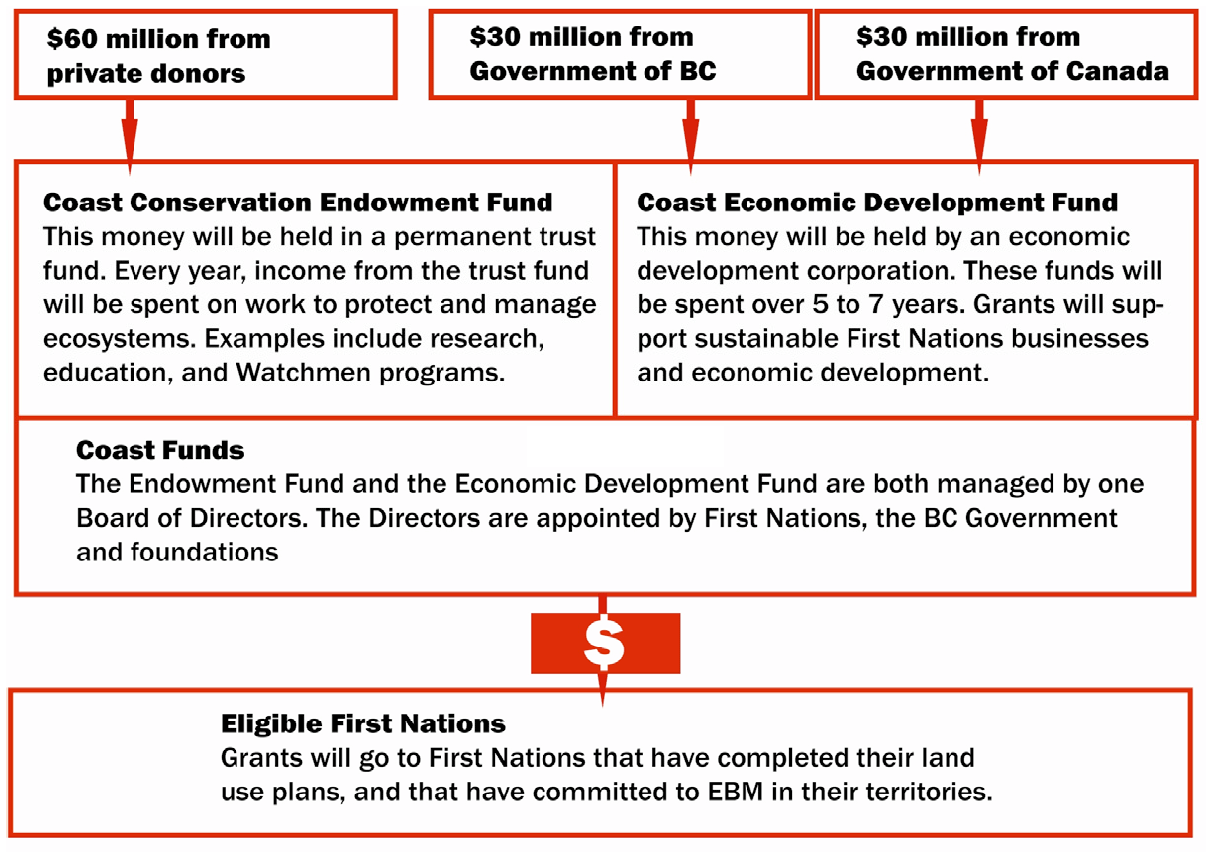

The 2006 agreements brought the Conservation Investments and Incentives Initiative’s vision closer to reality. Participation from the private philanthropy community brought funding commitments that were used to leverage government contributions. The Nature Conservancy, along with First Nations and environmental groups, played a central role in raising $60 million in private funds. The conservation financing concept would be borne out as two complementary streams of investment. First, $60 million dollars of private funds would be allocated to a conservation endowment fund would be dedicated solely to conservation management, science and stewardship jobs in First Nations communities. Second, $60 million dollars of public funds would be used to invest in sustainable business ventures in First Nations’ territories and communities.

Although the conservation financing structure was articulated in the 2006 agreements, it was not until a year later, in January 2007, that the Canadian and British Columbian governments each committed $30 million to the Initiative, matching the $60 million pledged by philanthropic donors and bringing the total available for conservation financing to $120 million.

The success of this initiative, which was considered an impossibility by some, demonstrates that complex issues can be resolved for the greater good of all British Columbians—not just for particular groups.

> Learn more about Coast Funds’ mandate.

Globally Significant Landmark Agreement Reached in 2016

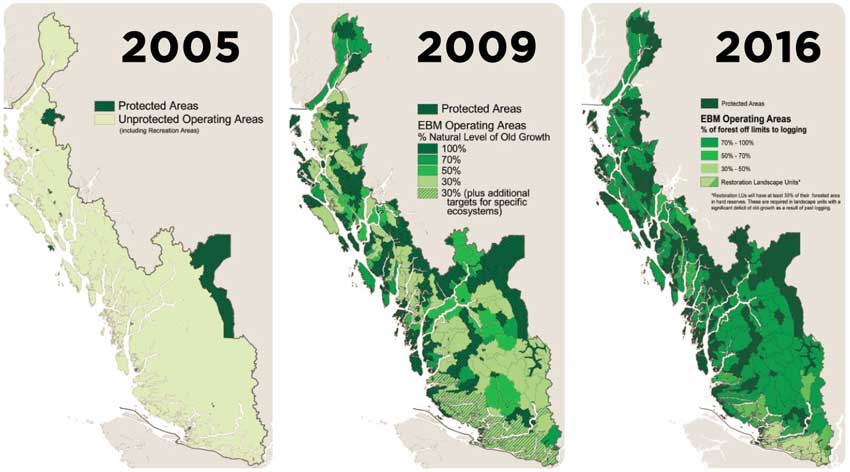

Under the new Great Bear Rainforest land-use order announced in 2016, ecological integrity is achieved through increasing the amount of protected old-growth forest to 70% from 50%. As well, eight new special forest management areas covering almost 295,000 hectares will be off-limits to logging. Six may receive additional protection based on ongoing discussions with First Nations. With the new measures, 85% of the forest will be protected and 15% will be available for logging, supporting local jobs.

The land-use order also addresses First Nations’ cultural heritage resources, freshwater ecosystems and wildlife habitat. The amount of habitat protected for the marbled murrelet, northern goshawk, grizzly bear, mountain goat and tailed frog will increase as new reserves required by the order are developed.

The Province has signed reconciliation protocols with the Coastal First Nations and Na̲nwak̲olas Council. Through these government-to-government relationships, separate human well-being agreements have been reached to address issues of special concern to each group of First Nations. Most notably, both have an increased stake in the forest sector.

Additionally, the Province has committed to amending atmospheric benefit-sharing agreements with Nanwakolas and Coastal First Nations. This will increase the forest carbon credits they can use to support implementation of ecosystem-based management and community development projects of importance.

Because of the uniqueness of the Great Bear Rainforest and the innovative elements in the new and amended agreements, the B.C. government introduced supporting legislation in spring 2016.

Resources

From Conflict to Collaboration: The Story of the Great Bear Rainforest

By: Merran Smith, ForestEthics, and Art Sterritt, Coastal First Nations;

Contributor: Patrick Armstrong, Moresby Consulting Ltd.

> See the Resources section for further information.

Historic Media Releases

Province Announces A New Vision For Coastal B.C.

Province of British Columbia, News Release, February 2006.

$120M for Coast Economic Development & Conservation

Province of British Columbia, News Release, January 2007.

Groundbreaking Conservation Investment Package Goes to Coastal First Nations

Coastal First Nations, April 2007.

New Vision for Coastal B.C. – Two Years Later

Province of British Columbia, Backgrounder, February 2008.

Globally significant landmark agreement reached

Province of British Columbia, News Release, February 2016.